Genocide in Gaza?

Shmuel Lederman

Translated by: Orit Schwartz

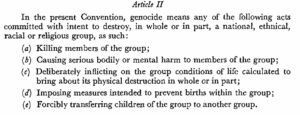

Over the last year, a broad consensus has emerged among scholars that Israel’s actions in Gaza constitute genocide. However, when discussing the definition of genocide, a distinction must be made between two different types of discourse: legal and scholarly. Since the authoritative definition of genocide in international discourse is the legal definition, much of the discussion focuses on the extent to which Israel’s actions meet the legal definition of genocide in the 1948 UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. The most important element of this definition is the intent to destroy a group in whole or in part. The Convention lists a number of acts that may constitute means to achieving this:

Contrary to the popular conception of genocide, which is largely shaped by theHolocaust and other prominent cases such as the extermination of the Tutsi in Rwanda or the Armenians during World War I, genocide does not necessarily mean an attempt to kill all or even most members of a group. Causing serious physical or psychological harm to group members, or a significant part of them, creating destructive living conditions, preventing births, and forcibly transferring children to another group may all constitute different means of genocide. Typically, these methods appear in combination.

Alongside the legal discourse on genocide, there is a scholarly discourse which tends to employ broader conceptualization and maintain a critical stance toward the legal definition, for reasons I will expand on later. Its roots trace back to Raphael Lemkin, the Jewish-Polish jurist who coined the term genocide. Although Lemkin sought to achieve recognition of genocide as a unique crime under international law, he understood the concept first and foremost as a historical phenomenon to be analyzed using all available tools – sociological, anthropological, psychological, and so on. Accordingly, his definition and description of genocide was significantly broader than that found in the UN Convention. For example, contrary to the legal definition, Lemkin saw the violent destruction of a group’s culture—including cultural works and sites, or prohibiting children from being educated in the group’s cultural traditions—as a central means of group destruction that could, in certain circumstances, itself constitute genocide.

The forced expulsion of a group from its land could also, under certain conditions, be considered a means of genocide according to Lemkin. More generally, Lemkin defined genocide as follows:

“…[G]enocide does not necessarily mean the immediate destruction of a nation, except when accomplished by mass killing of all members of a nation. [The term] is intended rather to signify a coordinated plan of various actions aiming at the destruction of essential foundations of the life of national groups, with the aim of annihilating the groups themselves. The objectives of such a plan would be disintegration of the political and social institutions, of culture, language, national feelings, religion, and the economic existence of national groups, and the destruction of the personal security, liberty, health, dignity, and even the lives of the individuals belonging to such groups. Genocide is directed against a national group as an entity, and the actions involved [in it] are directed against individuals, not in their individual capacity, but as members of the national group.”

For Lemkin, genocide is a process, an entire enterprise of destroying a group, of which the physical killing of group members is only the culmination. Historically, genocide constitutes, on the one hand, the culmination of a long process of constructing the victim group as a threat, and on the other hand, a response to trauma or the context of violent conflict. These factors lead to perceiving members of the victim group as an existential threat that can be tackled only by employing extreme violence aimed at destroying the group.

Furthermore, genocide emerges from Lemkin’s descriptions as an essentially colonial enterprise, or at least frequently so. A foreign nation takes over the territory of another nation or group and in the process destroys it in various ways to ensure permanent control of the territory. This occurs in two central phases: “The first, destruction of the national pattern of the oppressed group; the second, the imposition of the national pattern of the oppressor. This imposition, in turn, may be made upon the oppressed population which is allowed to remain, or upon the territory alone, after removal of the population and the colonization by the oppressor’s own nationals.”

Lemkin was not alone in this view. The recognition of genocide as a crime under international law was largely the result of a global movement that promoted this recognition. This movement included women’s organizations, Christian religious organizations, and international and American labor organizations. Representatives from African, Latin American, and Asian countries also joined, seeing themselves as victims of genocidal or similar practices at the hands of Europeans and others.

The legal concept of genocide, based on its definition in the UN Convention, is therefore significantly narrower than both Lemkin’s original conception and the broader definition that many historical victims of genocide have worked to promote. The legal definition sets an especially high bar for proving intent by key decision-makers to destroy the group, as well as for determining which actions may be considered genocidal. To a large extent, it was designed to protect the states that drafted it from potential accusations of genocide. For example, including cultural destruction could have exposed the United States and European colonial powers to genocide charges regarding indigenous peoples, while including political groups as a protected category under the Convention, could have led to accusations of genocide against the Soviet Union. For this reason, scholars who have examined the considerations and interests that shaped the drafting of the Convention have concluded that “it is no wonder […] that [the Convention] is so difficult to apply: it is designed to be a dead letter.”

Douglas Irvin-Erickson, one of Lemkin’s main biographers, summarizes the Convention’s drafting process as beginning with “an explicitly anti-colonial document and being transformed into something that colonial powers could tolerate.” In this sense, the history of the Genocide Convention reflects the broader history of the colonial roots of international law—a legacy that persists today. Many point to the historical tendency of international tribunals at The Hague to prosecute primarily African leaders. Others deemphasize the racist element and instead underscore the tribunals’ tendency to focus on non-Western leaders and states, or those not allied with the West, including figures such as Slobodan Milosevic and other war criminals from the wars that broke up the former Yugoslavia, or more recently, Russian President Vladimir Putin. These criticisms of the Convention and its application by international tribunals have long been common in genocide scholarship.

On the face of it, this broader discussion is irrelevant to the Gaza case. As Lee Mordechai rightly points out, it is difficult not to see Israel’s actions in Gaza as consistent with the legal definition of genocide. In legal terms, Gaza’s residents represent a “significant part” of the Palestinian people (the protected group under the Convention)—both quantitatively and qualitatively, given Gaza’s importance to the entire Palestinian people, as a space and community. Since the beginning of the war, many senior Israeli officials, from Netanyahu downward, have made explicitly genocidal statements targeting Gaza’s residents. This genocidal mindset has permeated significant segments of Israeli society and has been reflected in statements by journalists, key cultural figures, military officers, soldiers, and others. Alongside these statements, since the war’s beginning Israel has engaged in at least three acts specified in the Convention: mass killings, inflicting serious physical and mental harm on Gazans, and creating life-threatening conditions in Gaza.

To put this simply: the indiscriminate bombings have killed tens of thousands and wounded more than a hundred thousand people, many of whom are now disabled, while inflicting severe trauma on Gaza’s residents, especially children; The ongoing blockade and delay of humanitarian aid to Gaza has continued despite numerous warnings about its deadly consequences, and has even intensified since Israel violated the March 2025 ceasefire; and finally, the transformation of Gaza’s ethnic cleansing into an official war goal in recent months, in the form of implementing Trump’s plan of “voluntary immigration” from the Gaza Strip – all these are entirely consistent with the genocidal statements from the war’s beginning, and provide an almost perfect “case” for genocide even under the narrow legal definition.

However, regarding the question of genocidal intent, I believe Mordechai is correct in arguing that Israel’s Gaza policy throughout the war emerged not from a predetermined plan, but from a complex dynamic. This dynamic involved conflicting intentions among various decision-makers, an extremely permissive rules-of-engagement policy, widespread desire for revenge, and a command structure that gave ground-level commanders significant autonomy. Some of these commanders actively supported and implemented policies of ethnic cleansing or even outright genocide. As Mordechai argues, the crucial element is the “deep dehumanization in Israeli society toward Palestinians,” which has a long historical legacy. Politicians and mainstream media reinforced this dehumanization by cultivating the image of widespread support among Gazans, and Palestinians generally, for the October 7 atrocities, leading to the conclusion that there are no “innocents” or “uninvolved” civilians in Gaza. In this context, the genocidal manifestation of this dehumanization was almost inevitable. This complexity appears in other historical cases of genocide as well. The intent to destroy a group usually takes shape gradually, and sometimes remains unclear or ambiguous throughout the process. The destruction of the group or severe harm to it often emerge as the foreseeable result of policies aimed at other goals, rather than from a clear intention by decision-makers to destroy the group.

This analysis of the actual dynamics that have operated and continue to operate in the Gaza war is, at the very least, in tension with the legal definition of genocide, its dominant interpretations, and the precedent established by international court rulings on genocide cases to date. Therefore, while the destruction of Palestinian society in Gaza as a group is evident to any reasonable observer, and represents at least the foreseeable results of Israel’s policy since October 7, it remains uncertain how the court in The Hague will rule on the matter. And even if the court rules that this constitutes genocide, the high bar set by the legal definition ensures prolonged discussions on the issue. Meanwhile, Israel can persist in destroying Gazan society while its Western allies continue their support virtually unhindered.

Another aspect of this tension, stemming from a broader conception of genocide’s dynamics, is that Israel’s actions in Gaza cannot be separated from the all-encompassing extreme violence against Palestinians across all areas under its control. This includes the incremental killing and ethnic cleansing in the West Bank, the transformation of Israeli prisons into torture camps for Palestinian prisoners, the destruction of refugee camps, and the attempt to eliminate UNRWA along with Palestinian refugee status— effectively attacking Palestinian identity itself. This also includes the violent silencing of Palestinian citizens of Israel who seek to protest what is being done to their people. These and other actions are part of a broader assault on Palestinians as a group. While this attack manifests differently across various spaces, it can ultimately be understood, in Lemkin’s terms, as a “coordinated plan” aimed at destroying the Palestinian people, even though the most explicit genocidal acts are occurring in Gaza. Here too, the legal definition restricts our focus to only the most extreme acts, thereby ironically reinforcing the separation and fragmentation—physical, social, and mental—that Israel seeks to create and deepen between the various spaces in which Palestinians live under its control.

Paradoxically, then, the UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide makes it extremely difficult to prevent genocide. Gaza, to our horror, finds itself once again serving as a laboratory that exposes this troubling reality. Nevertheless, the very fact that the ICC in The Hague has issued arrest warrants for war crimes and crimes against humanity against Netanyahu and Gallant, and that the ICJ is hearing a case on genocide committed by Israel in Gaza, constitutes a historic landmark for the international legal system. How these cases are resolved may prove crucial, as they involve a country with deep military, economic, political, and cultural ties to the West—a country that enjoys unprecedented Western support and protection—now facing judgment in The Hague. In a sense, this represents a reenactment of the original struggle over the Convention: a global social movement seeking to prevent or reduce group extermination through binding international law, confronting powers that prioritize their political interests while paying lip service to a liberal and moral international order.

Shmuel Lederman specializes in genocide studies and political theory. He teaches at the University of Haifa and the Open University of Israel, and is assistant editor of the journal History and Memory and a research fellow in the Forum for Regional Thinking.

Additional Reading

Bachman, Jeffrey S. The Politics of Genocide: From the Genocide Convention to the Responsibility to Protect. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2022.

Graziosi, Andrea and Frank E. Sysyn (Eds.). Genocide: the Power and Problems of a Concept. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2022.

Irvin-Erickson, Douglas. Raphaël Lemkin and the Concept of Genocide. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016.

Irvin-Erickson, Douglas. “The “Lemkin Turn” in Ukrainian Studies: Genocide, Peoples, Nations, and Empire”. Genocide: The Power and Problems of a Concept, edited by Andrea Graziosi and Frank E. Sysyn, Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2022, pp. 145-173. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780228009511-008

Lemkin, Raphael. Axis Rule in Occupied Europe: Laws of Occupation, Analysis of Government, Proposals for Redress. Second Edition. New Jersey: The Lawbook Exchange, 2008.

Mordechai, Lee. Bearing Witness – Gaza. Last updated: July 5, 2025, https://witnessing-the-gaza-war.com/.

Straus, Scott. 2012. “‘Destroy Them to Save Us’: Theories of Genocide and the Logics of Political Violence.” Terrorism and Political Violence 24 (4): 544–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2012.700611.